How Do You Know When to Pull the Plug

For almost an hour, Nora Rangel's hubby and son hovered outside her infirmary room, hoping she could experience their presence through her sedation.

Tears came and went as they contemplated what the doctors were saying — that, more than a calendar month into her illness, the 63-twelvemonth-old was losing her boxing with COVID-xix.

A hospital case worker approached, proffering a form and a business card for hospice care.

Had they made a decision?

The visit was supposed to help them arrive at one. Only at this altitude, Nora's husband, Enrique, and son, Andy, couldn't discern how she was doing. Through the window, they could barely make out her face, and her motionless body was covered in a sheet. If only they could see her up close, Andy thought.

Heavy with worry, male parent and son walked to the parking lot, where Nora's other children were waiting. They decided they weren't fix to give up on Nora, the backbone of their family — mother of 4, grandmother of eight, married woman of well-nigh 44 years.

Not yet.

Vanessa Dyer, center; her sister, Alex Vasquez, and their father, Enrique Rangel, are brought to tears as their blood brother Andy Rangel tells Nora Rangel during a video telephone call that if she was tired, it was OK to go.

(Lisa Krantz, Staff Photographer | Express News)

As the coronavirus burned through San Antonio this summer, Nora's family confronted a series of agonizing choices while she deteriorated at Southwest Full general Hospital.

Many families were facing the same questions, making complex decisions about the medical care of loved ones from a distance. As infection rates soared, hospitals and other wellness care facilities adopted strict visitation policies that largely kept families from patients' bedsides.

The physical separation upended some of the most frail conversations in medicine, those between hospitals and families well-nigh the end of life.

Hospital staff fielded frequent calls from the families of seriously ill COVID patients, who were hungry for information and desperate for signs that their loved ones were recovering. They tried to bridge the gap through videoconferencing and daily telephone calls, but those workarounds could not fully supersede face-to-face conversations and extended fourth dimension at a patient's side.

How we did this

Lensman Lisa Krantz and reporter Lauren Caruba spent more than a month reporting on the family of Nora Rangel later on she fell critically ill with COVID-19. Before Nora's death, Krantz photographed her family unit during their video calls with her and equally they held a prayer vigil outside the infirmary. Krantz and Caruba both traveled to Del Rio in late July to attend her funeral visitation and burying. In addition to interviewing Nora'southward four children, Caruba also spoke with palliative intendance doctors and nurses, a pastoral care director and a bioethics expert.

"This is non normal, to be separated when your loved one may be dying," said Erin Perez, a palliative care nurse practitioner at University Hospital.

All this occurred during a menstruum of crisis for San Antonio's hospitals, where overworked staff cared for a alluvion of COVID patients.

The disconnect betwixt families and hospitals was made all the more than hard past COVID itself, a disease that can chart an unpredictable grade and pb to lengthy hospitalizations in the about severe cases. Blindsided by an illness no one could take planned for, families take had to grapple with the reality that those closest to them were suddenly dying.

Nora's family endured weeks of frustration and indecision. They struggled to understand how sick she was becoming. Different hospital workers relayed conflicting information about her status. During numerous calls among themselves and with her care team at Southwest General, they talked in circles about her prognosis.

At times, information technology felt like the questions they faced had no clear answers. Would a ventilator help or hurt? When was the correct fourth dimension to remove life support? How could they know for sure?

"Y'all read well-nigh so many stories of these people that have COVID for two months, three months, more. They're on ventilators even longer than my mom, and they're walking out of the hospital," said her other son, Henry Rangel. "What if we pull the plug likewise early? How tin can nosotros live with that?"

They decided to allow their faith guide them. All along, they were praying for a miracle.

Susie Medrano, with daughter Alexis Martinez, sings at the determination of a prayer for Nora, her slap-up-aunt, July 23 outside San Antonio's Southwest General Infirmary. Nora's husband and four children were joined by others in praying for her for close to an hour.

(Lisa Krantz/Staff Photographer | San Antonio Express-News)

Before the pandemic, the Rangel family gathered almost every weekend. There was regular traffic between Nora and Enrique'south house in Del Rio, where their daughter Alex Vasquez also lived, and the San Antonio area, domicile to her sons and other daughter, Vanessa Dyer.

At the centre of it all was Nora, whose given name was Leonor. She always seemed to exist worrying nearly everyone merely herself — cooking her children'south favorite meals, doting on her grandchildren and driving to Mexico to bring food and gifts to relatives.

Equally the coronavirus began spreading across Texas, the Rangels had to resist their instinct to exist together. It wasn't until a weekend in early on June that the unabridged family gathered at Vanessa's home in Helotes to gloat her twin daughters' second birthday.

In San Antonio, coronavirus cases and hospitalizations were ascension. They wouldn't begin to spike until the following calendar week.

Before the party, Henry developed a cough and felt fatigued. After hearing that a worker at a bar he'd patronized had contracted the coronavirus, he decided to go tested before seeing his family. The results were negative, but, nevertheless feeling tired, he stationed himself on the burrow.

The post-obit calendar week, Henry'due south symptoms worsened. Other family members began to fall ill.

Henry got tested once more. This time, it showed he was infected.

"I'chiliad sorry that I tested positive," he wrote in a group text to the family, urging them to get tested if they felt ill. "I never meant to put anyone at risk, especially the kids."

"I know this could have happened to whatsoever of u.s.a.," Vanessa replied.

"You didn't know you lot were really positive," Alex wrote adjacent. "In the cease it's our own responsibility to stay safe."

Vanessa and Andy were developing symptoms consistent with COVID.

By June nineteen, their female parent, a diabetic, had a fever, chills and fatigue. At STAT Specialty Hospital, a complimentary-standing emergency eye in Del Rio, she registered a fever and low oxygen saturation levels, though she wasn't struggling for breath. The hospital recommended Nora be monitored overnight.

Late that night, she was transferred by ambulance to Southwest General.

Vanessa, from left, Alex and their blood brother Henry Rangel mourn the loss of their mother, Nora, at Vanessa's dwelling house on Aug. 11. With Vanessa are her twin daughters, Sophia, left, and Olivia, ii. Nora died merely more than a month afterwards falling sick from COVID-19.

(Lisa Krantz, Staff Photographer | Express News)

***

The family's expectation that Nora would exist released quickly from the hospital dissolved.

She was presently transferred to the intensive care unit, where she spent a few days earlier being moved back to a regular room. Nora, who but spoke Spanish, didn't have admission to bilingual nurses. She kept her phone on her lap, and when she needed something, she called her daughters so they could contact the nurses' station on her behalf. She had to rely on a translation device to communicate with doctors.

Accustomed to being surrounded by loved ones, Nora frequently contacted friends and family unit. Each morning, she prayed with a friend by phone.

Her family unit members, meanwhile, were coping with their ain bouts of COVID. Andy grew depressed while isolating from his wife, son and newborn daughter. Henry'south affliction was serious enough to state him in a different hospital in San Antonio for 3 days. Enrique somewhen tested positive, too, but his merely symptom was lower back pain.

Over the adjacent two weeks, the responsibility of communicating with Nora and the hospital fell to Alex and Vanessa, who tested negative merely was still quarantining herself as a precaution.

On July 5, Nora told Alex the doctor had asked her about a motorcar but she couldn't provide further details. Alex called the nurse, who confirmed that Nora's doctor wanted to know how the family unit felt virtually placing her on a ventilator.

Later that twenty-four hours, a md told Nora's daughters that her organs were shutting downward, that she was dying.

Alex and Vanessa were shocked. They had been under the impression that Nora was fine. The other day, she had been sitting up on her ain. Over and over, the family unit had heard that her oxygen levels were skillful, non understanding that was due to increasingly aggressive oxygen therapy. They grew more confused when a nurse said that Nora's lungs were the only failing organ.

They wondered if the doc was talking near some other patient.

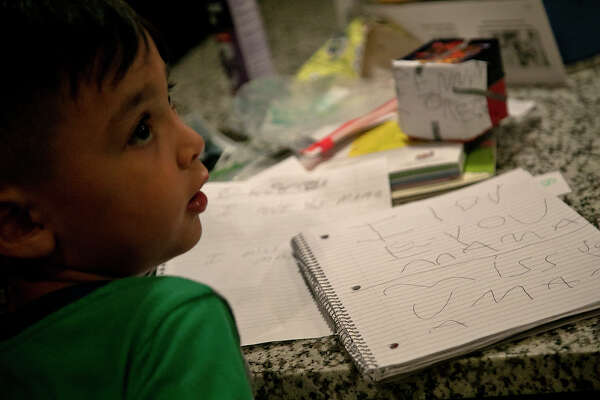

Clockwise from top:

Aiden Dyer, five, wrote a note to his "Mamá," Leonor "Nora" Rangel while his mother and other family members talked to her over FaceTime.

(Lisa Krantz | San Antonio Limited-News);

Vanessa, with her twins, Olivia and Sophia, and her son, Aiden, are joined past her sister, Alex, right, and Alex's son, Fabian Vasquez, 8, left, on a video telephone call with Nora.

(Lisa Krantz | Express News);

The nurses helped Nora videoconference with her family unit every night. Shown are Enrique, from left, Vanessa and Alex on a call with Nora.

(Lisa Krantz | Limited News);

Enrique, from left, Vanessa and Alex talk to Nora through a video telephone call that also included Andy and Henry. Nora was hospitalized with COVID-19 on June xix. She was put on a ventilator July x. Because of coronavirus restrictions, the family unit wasn't able to be at Nora's bedside during her disease.

(Lisa Krantz | Express News)

***

The next 24-hour interval, three of Nora's children drove to the hospital, intent on straightening things out. They expected to hear that it was all a misunderstanding.

Instead, as they crowded into a interruption room with the doctor, the message was the same: Nora wasn't probable to recover. They had two choices: give her medications and allow her to die comfortably, or transition her to a ventilator. The doctor wasn't optimistic that she would survive intubation.

Andy, Henry and Vanessa were immune to don protective gear to visit Nora, who was receiving oxygen through a BiPAP machine. Through the window to her room, Andy thought she looked exhausted, similar a prisoner. At her bedside, her children held her hand and offered words of encouragement, simply they didn't relay what the doctor had said. Isolated and unable to communicate easily with infirmary workers, Nora had already received anxiety medication.

When Alex and Enrique visited later that mean solar day, Nora was alert and joking. Alex could not believe the doc's dire prediction. To her, Nora looked and sounded potent. She evaded her mother'south questions near the ventilator.

"But if it'due south going to help me," Nora said of existence hooked to the breathing machine.

At Vanessa'south firm that evening, the family discussed their options, explaining to Enrique the choices the dr. had laid out. They agreed — being put on a ventilator wasn't what Nora wanted.

Nora'south family was sure their visit had done her adept. The next several days, she needed less oxygen and worked with a physical therapist.

Past the end of the week, it all fell autonomously.

Through a serial of frantic calls, the family learned the morn of July 10 that Nora wanted to be put on a ventilator.

When Alex finally reached her mother by phone, she explained that the procedure was risky. Nora, a devout Catholic, said she had faith in Jesus Christ.

"OK, Mom," Alex said. "We'll do it."

Nora'southward other children rushed to the hospital, where the procedure was already underway. Prepared for the worst, they frantically asked various nurses to check on her. They were relieved, and surprised, when one finally told them she was stable.

Felicitas Rangel, Enrique's mother and Nora's mother-in-police force, shares a moment with Miguel Hernandez during dejeuner Alex's home afterward Nora'south funeral. Nora and Enrique had been married nigh 44 years.

(Lisa Krantz, Staff Lensman | Limited News)

***

The family began researching experimental drugs and procedures to treat COVID, peppering hospital staff with questions, calling around to other hospitals.

Anything that could assistance save Nora's life.

They fixated on her ventilator settings, growing hopeful whatever time she needed less oxygen.

Each night, hospital staff gear up up an iPad in Nora's hospital room and so her family unit could talk to her through group video calls that eventually stretched to an hour long. They sang and prayed, hoping she could hear them through the sedatives.

After almost a week, Nora wasn't getting better. Andy got a phone call from a palliative care doctor, who asked whether the family unit had considered withdrawing life support.

The family wasn't fix to surrender.

Nevertheless, during one phone call, her children all told her the same thing.

"Mom, if you're done, you lot can rest. We're all going to be OK."

The next morning, the oxygen on her ventilator was increased to the maximum level.

The Rangels conferred again. This time, they decided that if she didn't amend shortly, they would remove her from the ventilator.

Days passed with little change. They couldn't bring themselves to brand the telephone call.

Doctors mentioned hospice intendance. The Rangels weren't interested in talking with the palliative care doctor, who didn't answer to their questions almost what was beingness washed to help Nora. Andy wanted answers, not attempts to persuade him that all options had been wearied.

The family bristled at doctors' suggestions that she was suffering. How could she be, if she was sedated?

"Y'all might be a doctor, but you can't tell usa that she'southward suffering," Henry said.

Andy didn't want his female parent to struggle. Could this exist the stop?

Then Vanessa and Alex said something that brought the family clarity.

Only God could determine when Nora died. It wasn't their place to choose.

Sophia Dyer, two, sits in front of the catafalque holding her grandmother, Nora, shown in photo at right, during the July 31 visitation and rosary at Trinity Mortuary in Del Rio.

(Lisa Krantz, Staff Photographer | Express News)

***

As the coronavirus reached into every corner of the state, it exposed the cracks in the U.S. health care system, said Serife Tekin, a University of Texas at San Antonio assistant professor who focuses on bioethics. That includes thorny discussions almost advanced directives — wishes about ventilators, resuscitation and quality of life subsequently a serious affliction or injury — which tin can be articulated formally in documents but remain an reconsideration for many families.

"This should serve as a learning lesson for the states, just like a lot of points in the history of medicine," Tekin said. "We need to use this moment to talk more proactively near stop-of-life decisions."

But the suddenness of San Antonio's coronavirus surge over the summer interfered with that.

Throughout July, more than 1,000 people were being treated for COVID in area hospitals on any given day. Hundreds were critically sick. To keep upwardly, hospitals brought on extra staff from contract agencies, the state health department and the war machine.

At Southwest General, three ICUs were opened just for COVID patients. At the height of the surge, the hospital had almost doubled its normal number of staffed beds, with help from effectually 150 visiting nurses. In many cases, staff, who were physically and emotionally exhausted, were working aslope strangers.

Decease was inescapable.

At Northeast Baptist Hospital, where Timothy Cranfill directs pastoral care, deaths were 60 percent college in July than the same month final year. The cumulative toll of ane decease afterwards another began to weigh on hospital workers, who at times felt helpless against the ravages of the virus.

Stuck on the outside, families might not have fully grasped the crisis hospitals were in or what was happening with their loved ones.

At bedside, family members can see swelling as excess fluid builds up in the body. They can hear the machines that are keeping the person artificially live. They can feel the person's hands, icy cold from medications that draw blood from the extremities to keep the heart pumping.

Take away that shut contact and families lose those clues about a person'southward status. Instead, they tin be left bewildered by the disease's progression, including sudden downturns that are a hallmark of COVID. Mixed messaging from different hospital staff, while non intentional, can inadvertently add to families' confusion about a loved one'south medical care.

In some cases, Cranfill said, the families of COVID patients have clung to "picayune pieces of hope" that their family unit member would be the exception to a devastating disease. Sometimes, hope can go desperation.

"The math simply doesn't add together upward across telephone lines," Cranfill said.

Enrique, left, watches every bit Deacon Adrian Falcon, from Our Lady of Guadalupe Church building, blesses Nora, his wife of almost 44 years, during her burial service at at Dusk Memorial Oaks Cemetery in Del Rio. Nora was hospitalized June xix with COVID-19. Coronavirus restrictions prevented Enrique and the residuum of the family unit from being at her bedside during her illness.

(Lisa Krantz, Staff Lensman | Express News)

***

Fifty-fifty nether the best of circumstances, discussions virtually seriously ill patients can forcefulness physicians and families into an uncomfortable spot, said Dr. Jason Morrow, a University Hospital palliative intendance physician and UT Health San Antonio acquaintance professor who helps lead the medical schoolhouse'south ideals curriculum.

Families don't want to hear bad news, and doctors don't want to give information technology. In that location is danger of sugarcoating the situation or being overly negative about it.

"Y'all tin can either empathize and be kind, or you can be the Grim Reaper," Morrow said. "And that feels like an unfair dichotomy."

To circumvent that, Morrow tries to connect with families equally soon as a person enters the ICU. He lays out two sets of milestones: the ones that would indicate the patient is recovering, and those that are worrisome. This approach, he has found, allows him to be factual during his daily updates with families, who already know the practiced signs and the bad.

Those indicators can help families brand choices that are guided past the patient's wishes, including whether they'd want farthermost life-saving measures.

At one point, Morrow treated an elderly man with COVID whose wife also was hospitalized with the virus. They had been married for the better office of a century, and his wife couldn't comport to let him become. But the homo, recognizing that his trunk was failing, had already decided confronting existence put on a ventilator. Before he died, hospital staff brought his wife to his room so they could hold hands and say their goodbyes.

-

Vanessa grieves the loss of her mother, Nora. Vanessa and her brother Andy were able to meet their female parent in person the evening before she died.

Vanessa grieves the loss of her mother, Nora. Vanessa and her brother Andy were able to see their mother in person the evening before she died.

Photo: Lisa Krantz, Staff Photographer

Vanessa grieves the loss of her mother, Nora. Vanessa and her brother Andy were able to encounter their mother in person the evening before she died.

Vanessa grieves the loss of her mother, Nora. Vanessa and her brother Andy were able to see their mother in person the evening earlier she died.

Photo: Lisa Krantz, Staff Photographer

Before the pandemic, Morrow would bring doctors and immediate family unit together in a room to talk over a critically ill person'due south prognosis. During these conferences, family members would frequently plough to each other with a common refrain: "What practise you lot remember?"

In the age of COVID, that couldn't happen. Morrow's communication with families now revolves around daily video calls, relegating complex conversations and emotions to a digital medium.

Morrow said he could see how a surge might pressure level hospitals to rush end-of-life decisions. Merely he is acutely aware that, to each family, but one person matters. He said daily video calls, while time-consuming, were the least the hospital could exercise under the circumstances.

At Northeast Baptist, i of the chaplain residents rigged an iPhone on a selfie stick to a remote-controlled car, so that families could videoconference with patients without health care workers having to enter the room for each call.

Steward Health Care, Southwest General's parent visitor, declined to annotate on the specifics of Nora'southward instance. In a statement, a spokesperson said the hospital "went to a higher place and beyond to provide compassionate care for this patient — and to go along the patient'due south family informed through regular communication during an incredibly emotional and difficult time."

Jonathan Turton, Southwest General's president, said the circumstances created by the pandemic were "simply impossible." Even as they followed state visitation guidelines and tried to augment communication through video calls, there was no fashion to fully meet families' need for information.

"Sure, they're talking to the nurse. They're having brusque, brief conversations with doctors that are carrying tremendous workloads," Turton said. "And they're still not getting plenty. Because even if they were getting accurate and complete information, information technology still doesn't see the emotional needs of, 'That is my family member. That is my loved one. I demand to know more. I need to run into more than.'"

Dr. Diana Fite, a Houston emergency room physician and president of the Texas Medical Association, said as the coronavirus raged across the country, member physicians complained about express visitation for the families of critically ill patients.

Visitation policies for hospitals, nursing homes and long-term care facilities were hastily drafted at the beginning of the U.S. epidemic, when at that place were still many unknowns near how the virus spread. In many cases, COVID patients couldn't have any visitors.

Such rules were intended to ensure safety, Fite said. Simply they failed to business relationship for the desperation this would put patients' families through, nor the stress that information technology would impose on doctors and nurses, some of whom were at a loss to explain the nuances of a all the same new disease.

On Aug. 12, Fite, along with leaders from the state'due south other medical professional person groups, asked the Texas Wellness and Human being Services Commission to allow daily visitation with patients who are probable near expiry or already in hospice care and in-person meetings to discuss their care.

Such a change would hinge on the availability of protective equipment for visitors and staff to guide them. But the public health crisis created past the coronavirus could final for years, the request noted, heightening the need for flexibility in stop-of-life situations.

"They're dying," Fite said. "There just has to be some consideration to the emotional and mental and spiritual aspect of all of this."

Nora'southward family say their goodbyes during her Aug. 1 burial at Sunset Memorial Oaks Cemetery in Del Rio. Shown are Alex, from left in front, Enrique and Vanessa, along with Andy Rangel, far right, holding his son, Sebastian, 2. Nora's children are grateful for the frequent video calls and the limited visits they did become, and that they were on the telephone with her when she died. But they wish they had understood the severity of her illness earlier during her hospitalization.

(Lisa Krantz, Staff Photographer | Express News)

***

On July 23, the Rangels and a small group of supporters gathered in the parking lot outside Southwest General. For an hour, they sang and prayed for Nora's recovery.

It was streamed to a Facebook page Andy created to collect prayers for Nora from friends and family. "Both doctors and the nurse believed that mom wouldn't survive the transition to the ventilator," he wrote on the folio's description. "Mom and God proved them all incorrect."

He had been posting daily updates on his mother'south condition, fervently maintaining organized religion that she would survive, even as her prognosis grew increasingly dire. The family wanted Nora to be put on dialysis, but doctors said she was as well delicate and it would only prolong the inevitable.

"The kidney dr. mentioned she wasn't showing any dilation in her pupils yesterday and believed she was brain expressionless," Andy wrote July 25. A nurse "likewise said that mom occasionally takes a breath on her own. I empathize these are tiny signs of life but they keep us hopeful."

The family unit had blanched at this assessment. Scared, they pressed doctors for more data.

"We want to know if she's encephalon expressionless and that's going to help our conclusion," Andy said, referring to his conversation with the physician. "And so he's similar, 'What does it matter if her lungs are already done?'"

That evening, a nurse chosen. Nora'southward blood pressure and oxygen levels were plummeting. The whole family got on a video call with Nora; and subsequently more than 3 hours, Andy and Vanessa got permission from the hospital to run across her in person. They remained on the phone with their family as they drove.

At the hospital, a nurse gave them gowns but blocked Vanessa when she attempted to open the door to Nora's room. He apologized as she began to cry.

They stood in the hallway for some time, until there were no staff in the area. Vanessa wanted to go inside, but Andy was hesitant. Other family members, yet on the phone, encouraged them to take the risk. What did they have to lose?

Vanessa made upwards her mind. She wasn't going to say goodbye through a window. She opened the door and quickly stole within.

When Andy went in next, he was finally close plenty to truly see what COVID had done to his female parent. He noticed how swollen her body had go, her chapped lips, the crust that had formed on her eyes and nose. He hugged her, ran his fingers through her hair and kissed her breadbasket. He traced the sign of the cross over her.

The hospital didn't have a clergyman, so before they left, they arranged for a priest in Del Rio to say a prayer by telephone. A nurse agreed to place a rosary in her room.

That night, Vanessa and Andy fell asleep immediately. They felt at ease.

Early the adjacent morning time, the hospital chosen again. Nora was fading. Her family rushed to get on a video phone call with her.

Within minutes, she was gone.

Clockwise from top:

Alex and her hubby, Roberto Vasquez Jr., comfort their son, Fabian Vasquez, 8, every bit he kneels in front of his grandmother'southward casket during the July 31 visitation at Trinity Mortuary in Del Rio.

(Lisa Krantz | Express News);

Andy pins a blossom on his father'south lapel before the Aug. ane funeral service for Nora, shown in the photo at right.

(Lisa Krantz, Staff Photographer | Express News);

Vanessa, eye, grieves for her mother during Nora's burial service. Her father, Enrique, is on the left.

(Lisa Krantz, Staff Photographer | Express News);

Alex, left, reaches out to her father, Enrique, during the burial service for Nora at Sunset Memorial Oaks Cemetery in Del Rio.

(Lisa Krantz, Staff Photographer | Express News)

***

V days subsequently, the Rangels filed into the Del Rio funeral home'southward chapel, where Nora's casket lay. Her visitation and rosary would brainstorm in a half-hr.

Masks were mandatory. Blueish tape roped off alternating pews to encourage physical distancing. A cordon of yellow tape created a buffer of several feet around her casket. A blueish surgical mask had been carefully placed on her face.

Shortly before their arrival, the funeral home director had chosen to inform them that the pare around Nora's mouth had been damaged by the ventilator and embalming chemicals. The mask was covering the disfigurement.

Nora's family understood that the mask was there to protect them from further pain. But information technology most added insult to injury, Henry thought, because how she died. He was also bothered by the barrier, which they hadn't been told about beforehand, and the idea that information technology could always keep him from touching his mother.

Ane by one, Nora's married man and children walked to the side of the catafalque where the bulwark didn't extend, so they could caress her face up, agree her hand and whisper in her ear.

Nora's 8-year-old grandson, Fabian, who had been particularly close to her, knelt at the casket. He bowed his head and began to cry, removing his glasses to wipe away the tears that fell in a higher place his mask.

For the next four hours, Andy found himself looking up at a screen on a wall, which was playing a slideshow of photos and videos of Nora. Lounging at the beach, celebrating holidays, holding her grandchildren, dancing in a purple dress. That was who his female parent was. Not this body that looked aught like her.

Less than a week after her funeral, Enrique and his children visited Nora's grave to mark their 44th wedding anniversary.

After the emotional roller coaster of Nora's illness, her children are grateful for the frequent video calls and the limited visits they did become, that they were on the telephone with her when she died. Not all families of COVID patients had such access, especially during the worst of the surge.

Even so, they wish they had known what questions to ask the infirmary. They wish they had before understood the severity of her illness. They wish the hospital had more clearly communicated to them what was happening.

The whole matter felt excruciating, fifty-fifty roughshod, Henry said. His mother was separated from her family when she needed them well-nigh.

"She deserved all of u.s. to exist at her bedside. That'southward what she deserved," Henry said. "Not to be alone, in a bed."

Vanessa leans her head on her father, Enrique, every bit her sister, Alex, lays an arm on her shoulder during the July 31 visitation and rosary for their mother and Enrique'southward wife, Leonor "Nora" Rangel, at Trinity Mortuary in Del Rio.

(Lisa Krantz, Staff Photographer | Express News)

Design past Joy-Marie Scott

Lauren Caruba covers health care and medicine in the San Antonio and Bexar County expanse. To read more from Lauren, become a subscriber. lcaruba@express-news.net | Twitter: @LaurenCaruba

Lisa Krantz is a national-award winning photojournalist at the San Antonio Express-News. lkrantz@express-news.internet | Twitter: @Lisakrantz

Subscribe

Real news. Real trust. Real customs. Subscribe to the San Antonio Express-News to support quality local journalism.

Today's Newspaper

Source: https://www.expressnews.com/coronavirus/article/COVID-19-decisions-about-death-15538800.php

0 Response to "How Do You Know When to Pull the Plug"

Post a Comment