| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

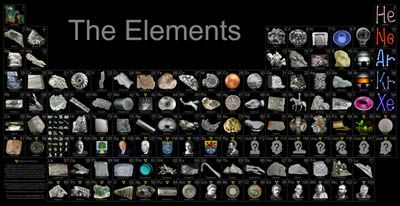

| My periodic table poster is now available! |  |  |  | |

|

| |

|

For many years I thought of magnesium as the thing that comes in ribbons which you can light with a match. This common school chemistry class demonstration produces a brilliant white light as the metal burns in air. It is usually followed by a somewhat less brilliant lecture about oxidation. When I first started hearing about things with magnesium cases, like the famous NeXT cube computers, it seemed a bit odd: I thought maybe they were talking about an aluminum alloy with some magnesium in it. I had a hard time believing when I read they were actually solid magnesium: Wouldn't it be a bit, um, dangerous if you could light your computer with a match? Well, it turns out that magnesium is only easy to light when it's in thin strips or powdered (as a powder it's even used in flash powder and fireworks). In solid lumps, it's actually really, really difficult to light, so difficult that it can take ten minutes with a blow torch to even get it to spark a bit (see below for a story about this). This is a good demonstration of how the physical form of a substance can have a huge effect on its properties. As a powder magnesium explodes, as a thin strip you can light it with a match, as a bulk solid you may never get the stupid thing lit. Same with corn starch: As a bulk solid you bake with it in a gas oven, as a fine powder it has been known to explode set of by no more than a spark of static electricity (this happens in grain elevators, which do not survive). | | | |

|

| |

|

|  | |    Bulk rod. Bulk rod. Bulk magnesium metal rod, about 1.25" diameter. No idea where it's from or what it was used for, but it burns nicely in shaving form. This one was purchased from eBay in May 2002. Ed Pegg and I spent an entertaining evening burning about 6 inches of one of these bars in two three inch sections. Click on the story book icon for this sample to see a bunch of pictures of burning magnesium rod. It's not what you expect. Source: eBay seller magman1000

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 29 May, 2002

Price: $6/pound

Size: 1.25"

Purity: >95% | |

|

|  | |   Engraved plate. Engraved plate.

I found a listing for a one inch thick magnesium plate on eBay. It was just a fraction of an inch bigger in each direction than the cover tiles in the periodic table (4.5" by 4.75"). When it arrived, I decided to see if I could machine it into an extra-thick replica of the magnesium cover tile. The edges were easily trimmed to the exact 4" x 4" dimensions of the tile using my compound miter saw (see the construction history page for more about this saw), and I used my tabletop belt sander to give all six faces a nice brushed satin finish.

Then came the moment of truth: Could my engraving machine (see history page) handle engraving magnesium? The answer is yes, with effort. The machine is meant to engrave plastic, and it works great with wood, but magnesium is pushing it in terms of the amount of force needed to move the cutter through the metal. The cutter itself is tungsten carbide and easily able to handle cutting non-ferrous metals. It's more a question of the strength of the pantograph arm. I think it could probably do aluminum and maybe copper, but not much more than that. Harder metals can be engraved using the diamond scratch engraving machine I keep in my office, but it just makes delicate lines, not deep grooves like these.

I applied a coat of clear acrylic varnish, because the metal tarnished almost immediately as I was working it. In fact, I had to put on gloves and go over all the surfaces with the belt sander one last time, because any place I touched it with bare fingers I left tarnish fingerprints. I polished the surfaces and then immediately varnished them to preserve the shine.

Source: eBay seller covers_machining

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 29 May, 2002

Price: $8

Size: 4"

Purity: >99% | |

|

|  | | Sample from the RGB Set. The Red Green and Blue company in England sells a very nice element collection in several versions. Max Whitby, the director of the company, very kindly donated a complete set to the periodic table table. To learn more about the set you can visit my page about element collecting for a general description or the company's website which includes many photographs and pricing details. I have two photographs of each sample from the set: One taken by me and one from the company. You can see photographs of all the samples displayed in a periodic table format: my pictures or their pictures. Or you can see both side-by-side with bigger pictures in numerical order. The picture on the left was taken by me. Here is the company's version (there is some variation between sets, so the pictures sometimes show different variations of the samples):

Source: Max Whitby of RGB

Contributor: Max Whitby of RGB

Acquired: 25 January, 2003

Text Updated: 11 August, 2007

Price: Donated

Size: 0.2"

Purity: 99.8% | |

|

|  | | Sample from the Everest Set. Up until the early 1990's a company in Russia sold a periodic table collection with element samples. At some point their American distributor sold off the remaining stock to a man who is now selling them on eBay. The samples (except gases) weigh about 0.25 grams each, and the whole set comes in a very nice wooden box with a printed periodic table in the lid. To learn more about the set you can visit my page about element collecting for a general description and information about how to buy one, or you can see photographs of all the samples from the set displayed on my website in a periodic table layout or with bigger pictures in numerical order. Source: Rob Accurso

Contributor: Rob Accurso

Acquired: 7 February, 2003

Text Updated: 29 January, 2009

Price: Donated

Size: 0.2"

Purity: >99% | |

|

|  | | Magnesium ribbon.

Magnesium ribbon can be lit with a match and it will then burn brilliantly and slowly along like a slow-motion fuse. It's really a very gentle, calm thing to see, though it will blind you if you look too long. Burning magnesium ribbon is a standard high school chemistry lab demonstration, to show that metals can burn. Iron burns too (you can light fine steel wool with a match), but magnesium burns a lot brighter.

Surprisingly, it's a little bit hard to buy magnesium ribbon: Standard lab supply companies won't sell it to private individuals. But other companies will (see the Source link).

Source: United Nuclear

Contributor: United Nuclear

Acquired: 11 April, 2003

Price: $7/roll

Size: 3"

Purity: >99% | |

|

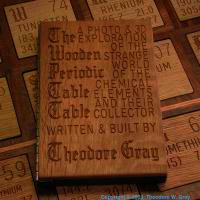

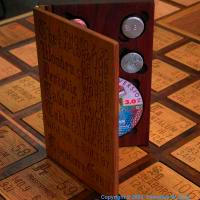

|  | |  Sample from Wooden Book. Sample from Wooden Book. Max Whitby and I talked about publishing a wooden book/CD/DVD/mini element collection, but it didn't go anywhere. It would have consisted of a nicely engraved wooden "book" with a CD and DVD version of the website (for those with slower internet connections), and a set of nine safe, interesting elements in the form of cylinders, cast blocks, nodules, and the like. Think of it sort of like a mineral collection, except it's an element collection and it comes in a much nicer box. Here are a couple of pictures of the prototype:   This cylinder is one of the samples that we plan to include in the product. Source: Max Whitby of RGB

Contributor: Max Whitby of RGB

Acquired: 12 May, 2003

Text Updated: 11 August, 2007

Price: Donated

Size: 0.5"

Purity: 99.9% | |

|

| |

|

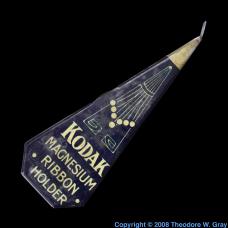

|  | |   Photographic ribbon holder. Photographic ribbon holder.

You might call this the world's slowest flash bulb. In the early days of photography film was not very sensitive and high-power flash lamps were not available. Exposure times would often be many seconds long, hence the stiff, formal look of portraits from that time: They were trying not to breath. Magnesium powder was used in flash powders (where the photographer held a pan up over his head and lit it, resulting in a bright flash and a poof of smoke). A safer, more controllable alternative was to use magnesium ribbon, which burns very brightly, and at a consistent rate. The idea behind this holder is that you use it to measure out a predetermined length of ribbon, calculated to generate the amount of light you need to expose your film (based on the brightness and the rate at which the ribbon burns). You pull that much ribbon out of the holder (which has a spool inside), then light it. When the flame reaches the tip of the holder, it goes out, automatically timing your exposure. In other words, a slow-motion flash bulb.

I paid a lot of money for this, $100, but that seems to be the going rate: Several similar ones have sold on eBay in this price range, and this is a really nice one with the original box and instructions intact.

Source: eBay seller sport1

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 15 December, 2003

Text Updated: 29 January, 2009

Price: $100

Size: 4"

Purity: 99% | |

|

|  | | Hollow cathode lamp.

Lamps like this are available for a very wide range of elements: Click the Sample Group link below to get a list of all the elements I have lamps like this for. They are used as light sources for atomic absorption spectrometers, which detect the presence of elements by seeing whether a sample absorbs the very specific wavelengths of light associated with the electronic transitions of the given element. The lamp uses an electric arc to stimulate the element it contains to emit its characteristic wavelengths of light: The same electronic transitions are responsible for emission and absorption, so the wavelengths are the same.

In theory, each different lamp should produce a different color of light characteristic of its element. Unfortunately, the lamps all use neon as a carrier gas: You generally have to have such a carrier gas present to maintain the electric arc. Neon emits a number of very strong orange-red lines that overwhelm the color of the specific element. In a spectrometer this is no problem because you just use a prism or diffraction grating to separate the light into a spectrum, then block out the neon lines. But it does mean that they all look pretty much the same color to the naked eye.

I've listed the price of all the lamps as $20, but that's really just a rough average: I paid varying amounts at various eBay auctions for these lamps, which list for a lot more from an instrument supplier.

(Truth in photography: These lamps all look alike. I have just duplicated a photo of one of them to use for all of them, because they really do look exactly the same regardless of what element is inside. The ones listed are all ones I actually have in the collection.)

Source: eBay seller heruur

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 24 December, 2003

Price: $20

Size: 8"

Purity: 99.9%

Sample Group: Atomic Emission Lamps | |

|

| |

|

|  | |   Antique powder flash. Antique powder flash.

This is a very old magnesium powder flash. The seller stated the following: "Not sure on the age, but it's prewar. Came from my grandfather who had a photo in the late 20s to the 30s." I have no reason to doubt this, and the instruction sheet does not contain any dates to confirm or deny the age claim. The instructions do, however, use the name I.G. Farben, a company which was dismantled by the allies in 1951, which puts a lower limit on how old it could be. (Why, you may ask, was I.G. Farben dismantled by the allies? Because it was one of the principle industrial engines of the Nazi death machine, being as it was a major financial supporter of the Nazis as well as the producer of the Zyklon B used in their gas chambers.)

The instructions say to mix the powder in the small glass vial (which is an oxidizer of some sort, perhaps potassium permanganate) with the magnesium powder in the tin, hang the tin up with its strap, then stick the provided paper fuse into the powder and light it. This is a single-use flash: I assume you would normally have a pack of several of these with you.

Source: eBay seller oakwilde

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 25 October, 2005

Text Updated: 29 January, 2009

Price: $38

Size: 1.25"

Purity: 95% | |

|

| |

|

| |

|

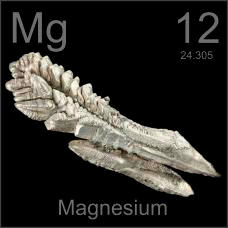

|  | |   Crystal. Crystal. Warut sends me two kinds of things every once in a while: Emails linking to eBay items which I invariable end up spending money on, because he has such a good eye for things I will want. And actual element samples, like this pretty little magnesium crystal. It broke off a much larger crystal he got from China, and while I would of course love to have a great big crystal like his, this one is actually an ideal size for photography, because you can see the fine detail that would be invisible in a photograph of a larger sample. The 3D rotation video of this sample is particularly attractive. I don't know the origin of this material other than that it's from China, but I would speculate that it's from an electrolytic refining process, and would probably normally have been melted down into useful products. Reader Eric Winter has kindly pointed me to this article which indicates it's probably vapor deposited in the "Pidgeon process". I chose this sample to represent its element in my Photographic Periodic Table Poster. The sample photograph includes text exactly as it appears in the poster, which you are encouraged to buy a copy of.

Source: Warut Roonguthai

Contributor: Warut Roonguthai

Acquired: 5 November, 2005

Text Updated: 7 April, 2009

Price: Donated

Size: 2.5"

Purity: 99.9% | |

|

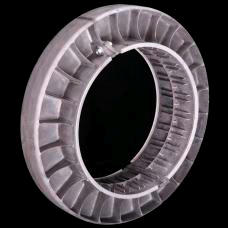

|  | | Humvee Run-flat.

This gorgeous (in a rough sort of way) bit of magnesium casting is an insert designed to go inside the tire of a military HMMWV (pronounced Humvee) to keep the vehicle moving even if the tire blows out. I assume it's made of magnesium because when wheels are spinning very fast, every bit of extra weight increases the gyroscopic effect when you attempt to turn the wheels. Magnesium is quite commonly used in race cars and high-end sports cars because of its light weight.

The fact that it's also flammable would seem like a disadvantage particularly in a war zone, but actually solid magnesium is surprisingly hard to light. (I have a story about the relative flammability of different forms of magnesium.)

This stuff is definitely real, fairly pure magnesium. I have a third half-wheel that came with the set in the photograph, and a small chip broken off that one lit and burned exactly like real magnesium. Amusingly these were actually offered on eBay as camp fire starters: Any block of magnesium can be used that way by scraping off some curls of metal with a hunting knife, then lighting them with a flint. But eBay canceled the listing for violation of some policy or other (not sure which one, since camp fire starters are routinely sold on eBay, as well as at Walmarts all over the country).

I don't even want to know what the military originally paid for these things, but I think $10 per half-wheel is a pretty fair price for such a lovely bit of magnesium.

Source: eBay

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 26 June, 2006

Text Updated: 29 January, 2009

Price: $20

Size: 24"

Purity: 98% | |

|

| |

|

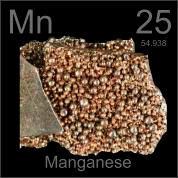

|  | |   Nodules. Nodules. I didn't really understand until recently where these nodules came from. People in China are selling bunches of them, and they are very beautiful. I thought they must be electrowinning nodules (built up by electroplating), considering how similar they look to the nickel and copper electrowinning nodules I have. Fortunately reader Eric Winter has kindly pointed me to this article which indicates they are probably vapor deposited in the "Pidgeon process". Source: eBay seller artgarden2005

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 16 December, 2006

Text Updated: 9 April, 2009

Price: $10

Size: 3"

Purity: >90% | |

|

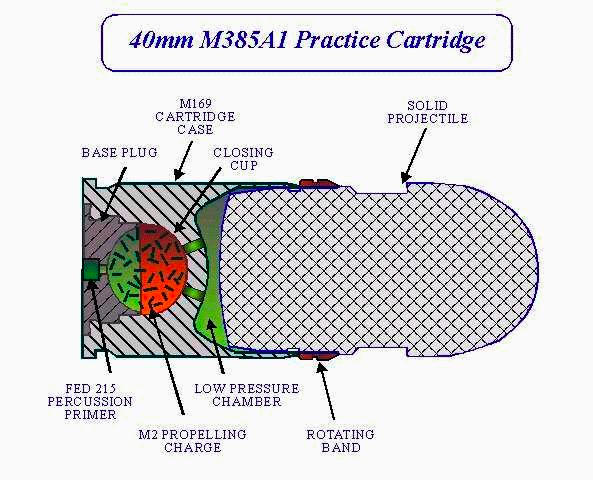

|  | |   Dummy round. Dummy round. This is a round from some kind of really big gun. It was described as a magnesium practice round, and it has holes drilled in the shell casing that would make it impossible to use in a actual gun, if you had one that big. I'm not clear whether the "magnesium" refers to its being a magnesium incendiary projectile, or that it's made of magnesium because it's a practice round. Neither actually makes a whole lot of sense to me, so hopefully someone will recognize it and tell me more about it one day. And guess what, reader David Neri helpfully identified exactly what the thing is, and even found three pictures of it.

This diagram from the Federation of American Scientists shows a cross section of the innards:

This picture from the iStockPhoto shows a whole belt of them:

And this picture from the Aircav shows the gun it was used in:

The last source says that these are actually made of aluminum, which seems more sensible than magnesium, and more consistent with the sample I have, which appears to be aluminum. But I never move samples once listed, so this one is still under magnesium. It's quite possibly made of a magnesium-aluminum alloy with a few percent of magnesium, so I'm speculatively listing it as having at least a bit of magnesium. (People often refer to aluminum alloys with a bit of magnesium as "magnesium", for example "mag wheels" are often actually aluminum, though genuine all-magnesium wheels also exist.) Source: eBay seller chrisredcat

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 17 February, 2007

Text Updated: 11 August, 2007

Price: $22

Size: 4"

Purity: <10% | |

|

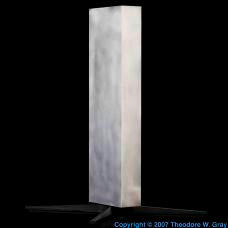

|  | |   Monolith. Monolith.

This is a huge (33.5" x 10" x 4") slab of pure magnesium was probably intended as a billet (stock) to be machined into a part of some sort for a race car, motorcycle, or other such application. I just sanded it smooth and put some varnish on to make stay shiny, then mounted it on a set of cast iron table legs so it could stand upright in my office. Drilling and tapping a hole for a 1/2" bolt in the bottom was child's play: It's softer even than aluminum. And I confirmed that it really is mostly pure magnesium by lighting the chips from drilling the hole.

The slab (which, incidentally, looks a lot like the one in the movie 2001 except not black) weighs 87.5 pounds, which isn't much for a slab this big: Magnesium is pretty light as metals go. If it were made of iron it would weigh 380 pounds, out of tungsten it would be 934 pounds, out of osmium 1094 pounds.

Source: eBay seller boss1

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 12 May, 2007

Text Updated: 12 May, 2007

Price: $218

Size: 33.5"

Purity: >95% | |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|  | |   Actinolite asbestos. Actinolite asbestos. The name "asbestos" used to mean a wonder-material, an insulator without equal and a strengthening fiber so cheap and strong it was used in building materials worldwide. Today the name means nothing but death and ruin. Asbestos had been used so widely and for so long that it must have seemed beyond credibility when evidence first started appearing that it might be harmful. It is, after all, just a natural mineral, a rock dug from the ground. It contains no toxic elements or compounds. As a silicate mineral, asbestos is a member the group of minerals that make up as much as 90% of the earth's crust. How could such a common rock possibly be dangerous? The answer lies in its shape. As you can see from this and the other asbestos samples below, the difference between asbestos and other silicate minerals is that asbestos appears in the form of very fine hair-like fibers. This fibrous nature is what makes it so useful as an insulator and building material: It can be woven, braided, pressed into mats, or mixed with plaster or concrete to make a strong, fiber-reinforced material. (It's also fireproof and impervious to most chemicals: What more could you ask for? To this day there are no really satisfactory substitutes for some applications from which asbestos has been banned.) The fibers are not just fine, they are ultra-fine: The ends of the natural fibers taper down to molecular sharpness, with a tip that is literally no more than a few atoms across. Lodged in the body, most commonly in the lungs when stray fibers are inhaled, these tips can worm their way into individual living cells and tickle the DNA in a way that no blunt artificial fibers can. The ability to touch, and damage, DNA makes asbestos fibers potent carcinogens: Remarkably, unlike virtually all other carcinogens, they cause cancer purely mechanically, not chemically or by radiation. They literally poke the strands of DNA in a living cell without killing the cell. Topping off their deadly potential, asbestos fibers, unlike for example modern fiberglass fibers, last pretty much forever in the environment of the lungs. Fiberglass is said to dissolve after a few months in the lungs, and in any case isn't sharp enough to cause molecular-level damage (at least, that's what people think now, we'll see how the evidence stacks up in another 50 years). But asbestos fibers will sit there for decades on end, firmly lodged in the deepest recesses of the lungs, just waiting for some unlucky DNA to happen by. In principle asbestos could cause cancer anywhere in the body, but it's the lungs that are most vulnerable. As with many hazards, its layer of dead cells protects the skin from asbestos, as does the lining of the gut. But in the lungs the living cells are right on the surface, vulnerable to anything that finds its way past the nose and sinuses. The most serious disease caused by asbestos is mesothelioma, a form of cancer. If you look up mesothelioma in google, you will find lawyers, lawyers, and more lawyers. Everywhere you look, it's lawyers as far as the eye can see. Even websites that seem to be purely informational or medical in nature will, on closer examination, turn out to be sponsored by a law firm. The reason of course is that there is big money in mesothelioma, specifically in suing any and every company that ever had its doorstep darkened by a product containing asbestos in any form. There is probably some guilt in the asbestos industry. The real truth will most likely never be known, since to admit it would mean instant financial ruin for anyone who spoke, but my guess is that some people, including some senior people at large companies, knew pretty well that asbestos was harmful, and instead of immediately shutting their companies down and putting hundreds of people out of work, they tried to hide the evidence and thus condemned more workers and customers to death. (Business is complicated, much like life.) But the current orgy of asbestos litigation is clearly targeting people far from any reasonable definition of guilt. Lawyer's websites list literally hundreds of companies and job sites, including small plumbing distributors, hospitals, schools, and even court houses. All places where asbestos was manufactured, sold, handled, or used. All places liable to being sued for millions of dollars by someone who wishes to hold them accountable for the disease that is slowly but surely killing them. Saying that a small plumbing company that sold or installed asbestos insulation is liable for the illness of its workers or customers throws common notions of liability on their head. These small business people had no more reason to believe asbestos was dangerous than did their employees and customers: No one imagined it. No one considered it. No one would have believed it. And if some large companies had internal documents suggesting there was cause for concern, they certainly didn't share those with the local plumbing contractor! A lot of good people have been ruined by asbestos litigation. But a lot of people have died because of asbestos, and juries tend to want to find a way to help sick people, even if it means extracting money from someone who did nothing wrong, someone whose only guilt is being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Which is to say, being the owner of a business that sold a legal product that they and everyone they knew thought was safe. What would be a fair solution? Society benefitted from asbestos, society (which is to say the government) should pay to take care of those harmed by it. In most countries, that's just what happens (and not just for asbestos-related disease). But in America, we instead have a system in which we pick random companies and extort them for sometimes more money than they have, to enrich a few sick people beyond any reasonable need, while diverting a large percentage of the money to lawyers who, much as some people might wish it, don't even have mesothelioma. Those not lucky enough to find a target with deep pockets, or too honest to blame a blameless party for their misfortune, languish in poverty and pain until death takes them. It makes about as much sense as throwing darts at a board to decide who pays for which disease: OK, Amtrack, you pay for lupus, General Motors gets colon cancer, Microsoft can take gastroenteritis, Chiquita gets mesothelioma, and for hives we will pick, oh, say, McDonald's. (Yes, Chiquita Bananas is on the list of companies targeted for asbestos litigation. The other company-disease associations I made up and have no basis in fact. So far as I know.) One thing that is often missed in discussion of asbestos is that the minerals it comes from are beautiful! I bought a set of six absolutely stunning mineral samples representing the range of natural sources for this amazing product. The photo associated with this text is of Actinolite, one of the most potently carcinogenic forms of asbestos. Its sharp, needle-like fibers make it especially dangerous. The samples below represent all the major natural sources of asbestos fibers. Mineral details: Actinolite (variety "Byssolite"), amphibole group, double-chain silicate. From the Greek aktinos ("ray"). French Creek, Chester County, Pennsylvania, USA. Source: eBay seller star-stuff

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 10 April, 2006

Text Updated: 1 June, 2006

Price: $30

Size: 2"

Composition: Ca2(MgFe)5Si8O22(OH)2 | |

|

|  | |   Anthophyllite asbestos. Anthophyllite asbestos. See above Actinolite sample for an extended discussion of asbestos, mesothelioma, lawyers, and litigation. Anthophyllite asbestos is quite rare: This mineral was not used as commonly as the others listed here. Mineral details: Anthophyllite, amphibole group, double-chain silicate. From the Latin Anthophyllum ("clove"). Carleton Talc Mine, Windsor County, Vermont, USA. Source: eBay seller star-stuff

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 10 April, 2006

Text Updated: 30 May, 2006

Price: $30

Size: 2"

Composition: Mg7Si8O22(OH)2 | |

|

|  | |   Chrysotile asbestos. Chrysotile asbestos. See above Actinolite sample for an extended discussion of asbestos, mesothelioma, lawyers, and litigation. The mineral chrysotile is the basis of the most widely used form of asbestos, and the safest. In fact, this form of asbestos is still in current production in many parts of the world and is considered safe by many people and organizations (though not by all). It is chemically and physically different from all the other minerals used in asbestos (see samples above and below). The others are Amphibole silicates while chrysotile is a serpentine mineral. Whether it is completely safe or not depends on the form it's in (and on who you ask), but it is generally agreed that chrysotile is the least potent carcinogen among the asbestos minerals. Mineral details: Chrysotile, serpentine group, sheet silicate. From the Greek chrysos ("gold") + tilos ("fiber"). Thetford Mines, Quebec, Canada. Source: eBay seller star-stuff

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 10 April, 2006

Text Updated: 30 May, 2006

Price: $30

Size: 2"

Composition: Mg3(Si2O5)(OH)4 | |

|

|  | |   Grunerite asbestos. Grunerite asbestos. See above Actinolite sample for an extended discussion of asbestos, mesothelioma, lawyers, and litigation. Mineral details: Grunerite (variety "Amosite"), amphibole group, double-chain silicate. Name is derived from an acronym of an original mining locality (AMOSA Mine, Asbestos Mines Of South Africa). Sample from Limpopo Province, South Africa. Source: eBay seller star-stuff

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 10 April, 2006

Text Updated: 30 May, 2006

Price: $30

Size: 2"

Composition: (FeMg)7Si8O22(OH)2 | |

|

|  | |   Riebeckite asbestos. Riebeckite asbestos. See above Actinolite sample for an extended discussion of asbestos, mesothelioma, lawyers, and litigation. Mineral details: Riebeckite (variety Crocidolite), amphibole group, double-chain silicate. From the Greek krokid ("nap on woolen cloth"). Kuruman, Northern Cape Province, South Africa. Source: eBay seller star-stuff

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 10 April, 2006

Text Updated: 30 May, 2006

Price: $30

Size: 2"

Composition: Na2Fe2(FeMg)3Si8O22(OH)2 | |

|

|  | |   Tremolite asbestos. Tremolite asbestos. See above Actinolite sample for an extended discussion of asbestos, mesothelioma, lawyers, and litigation. Mineral details: Tremolite, amphibole group, double-chain silicate. Named after the type locality at Val Tremola (Gotthard Massif, Switzerland). Sample from Placer County, California, USA. Source: eBay seller star-stuff

Contributor: Theodore Gray

Acquired: 10 April, 2006

Text Updated: 30 May, 2006

Price: $30

Size: 2"

Composition: Ca2(Mg)5Si8O22(OH)2 | |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| My periodic table poster is now available! |  |  |  | |

Bulk rod.

Bulk rod.  Engraved plate.

Engraved plate.

0 Response to "Short Story About Calcium and Magnesium Funny"

Post a Comment